Burt Bacharach

May 12, 1928 – February 8, 2023

An Appreciation

By Alex Rybeck

Every popular art form has its masters and monuments. We just lost a modern master of American popular song, Burt Bacharach, but the monument (his vast output of music), like the ocean, isn’t going anywhere. Varied and immeasurably influential, his music has been embraced for decades by anyone who has a heart.

In looking at the rise and development of the pop song in America, we can see a lineage that includes Berlin, Kern, Rodgers, Arlen, Porter, Ellington, and, just as the rock era emerges, Bacharach, someone with one foot in tradition and the other firmly in “today” and beyond.

The key to understanding Burt’s “sound” is that it’s a melting pot of influences: classical music (especially Debussy and Ravel), Brazilian bossa nova (a big craze in the early 1960s), the R&B of groups like The Drifters and the Shirelles (often from the pens of Lieber and Stoller), and even European chanson, which he encountered while touring with and conducting and arranging for Marlene Dietrich. Burt had a restless, curious ear that had absorbed everything from the bebop jazz of Dizzy Gillespie to the thorny dissonances favored by contemporary “serious” composers in the mid-20th century. In his heart, Burt was a romantic who had a passion for melody.

He often told the story of studying composition with Darius Milhaud and being a bit embarrassed to play for the class one of his assignments because it was unabashedly melodic at a time when tonal music was out of fashion for anyone “serious.” To Burt’s surprise, Milhaud responded by saying, “Never be ashamed to write something that someone can whistle and remember.” Burt never forgot that. (And is it an accident that “Magic Moments,” one of his earliest hits, opens with a catchy motif that is literally whistled?)

On a personal note, I became aware of the standout “Bacharach sound” via the equally outstanding and unforgettable voice of Dionne Warwick when I was seven years old. The year was 1964. The lyric may have admonished me to walk on by, but the music stopped me in my tracks. Rooted to the spot, I was transported, bewitched—me and millions of others. And to this day, at age 65, I am still transported, bewitched.

Burt’s restless, curious ears led him to create a unique musical language, defined by elegance coupled with unpredictability. People say (with justification) you can identify a Bacharach song within a few bars. I think it’s the beguiling dichotomies: it soothes and seduces with lush strings and background vocals, then teases and provokes with unexpected instrumentation (a flugelhorn? a scraped gourd? a tack piano? a euphonium solo?), asymmetrical melodic phrases, sly shifts of time signature, and daring harmonic progressions previously unheard in the context of popular music.

It’s a delicate balancing act: popularity vs. innovation. It’s also a fine line between what feels comfortable (smooth, groovy) and the cloying morass of “easy listening.” Burt mustn’t be blamed for the fact that his tunes were appropriated by hack arrangers who served them up in elevators and dentists’ offices. Burt’s great appeal to the public, along with a mantel overloaded with Grammy’s, Oscars, and other top awards, has sometimes had unfortunate effect of disguising the sheer quality and innovative aspects of his work. Non-musicians can simply enjoy the feelings his songs evoke, while at the same time, schooled musicians and critics can (and do) appreciate his complexity and the intricacies of his compositions.

Make no mistake; even his two-and-a-half minute songs are compositions, meticulous, exploratory, full of detail and crafted. Most rock-derived pop songs are built on the notion of simplicity and repetition—single key, groove, “hook,” repeated without variation. Burt’s ears and temperament were too sophisticated and refined to tolerate the raw, numbing bludgeoning of repetitive rock. He would sometimes describe the way a song can “beat you up,” which was what he tried to avoid in his own work. He liked to describe what he did as making mini movies for the ear, dramatic soundtracks with emotional peaks and valleys. One song could contain passages of quiet, folk-like beauty only to suddenly swell into symphonic grandeur and then subside again.

Given the inherent theatricality of his music, many wonder why he never wrote for Broadway following his smash hit, Promises, Promises (1968). For one thing, writing a musical takes a lot longer (often years) than turning out a single song. He much preferred the instant gratification of finishing a song and then going directly into the recording studio to capture it and release it. Done! For another thing, there was the issue of control. Studio sessions gave Burt the power and control his music demanded.

After as many “takes” were necessary, he could achieve the best possible result from singer and orchestra, preserved that way forever. On Broadway, from night to night there are variations, inevitable when you may have a substitute drummer or trumpet player, or conductor, or leading lady. Wrong tempos, sour notes—these were unbearable to Burt, who always wanted his music to be heard to best advantage. It was a case of self-preservation.

One last thing: it’s time to stop relegating Burt to the 1960s or even exclusively to his successful partnership with Hal David, an often-underrated lyricist who was, in his own unassuming way, another giant of pop writing. The truth is Burt’s music was (and is) revolutionary, and it did not depend on any single lyricist for its intrinsic distinction. Burt collaborated with many fine writers before and after Hal (Mack David, Carole Bayer Sager, Elvis Costello, Steven Sater, Daniel Tashian, among others), but his music was always true to its own heartbeat. Burt was always consistently Burt-recognizable: appealing, yearning, offbeat, relatable, fresh, and surprising, and now and forever relevant. Or to put it another way, just what the world needs now—and always.

New York City

February 2023

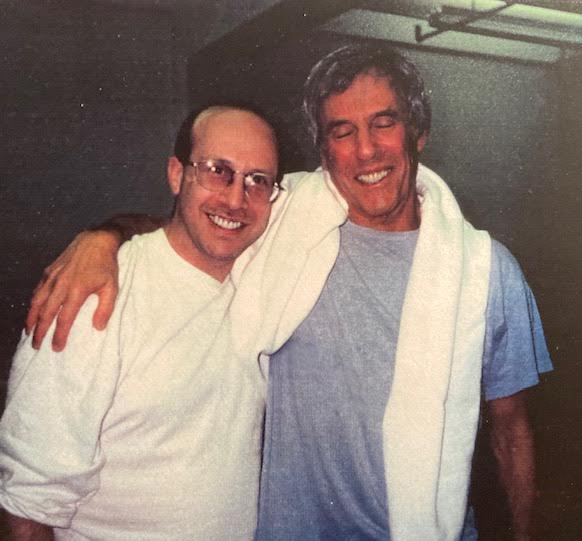

Alex Rybeck is a composer, pianist, and arranger, who served as Musical Director for What the World Needs Now, a musical based on the Bacharach/David songbook, which played the Old Globe in San Diego in 1998 and starred Sutton Foster.