27th New York Cabaret Convention

Saluting Sylvia Syms

Rose Theater, NYC, October 20, 2016

Reviewed by Rob Lester for Cabaret Scenes

Photos by Eric Rudy

The answer to the tentatively or even apologetically posed question from newbies each year at the Cabaret Convention or cabaret shows in more typically small venues rather than Jazz at Lincoln Center’s big Rose Theater is this: “Um, so what exactly distinguishes ‘cabaret’ as an art form/style/genre/approach compared to other ways of singing a song?” Experiencing the more thoughtful and mature renditions by singer Sylvia Syms would have been the demonstration of the standard answers about how cabaret artists handle the standards: It’s all about phrasing. The singer delivers the lyricist’s own words as if she’s thinking out loud and these are her own thoughts in the moment, shared privately, one on one, just with YOU, a single person in the audience who will connect, consider, cogitate, cry, crinkle up in conspiratorial smiles. So the shadings are fresh, shining subtle new light on the familiar, with accompanists seeming to be breathing along with that vocalist, in the same shared emotional space. Not an easy trick, especially when you know those words by heart yourself. For the third night of the Mabel Mercer Foundation’s annual Cabaret Convention, Syms was simply a wise and classic example of this approach as she, like the exalted Miss Mercer herself. And Sylvia Syms was feted with finesse and fondness by Rex Reed, chatty cum and host of the evening, joined by singers, some of whom knew Miss Syms, who passed away in 1992. She died quite dramatically, having a heart attack immediately after ending her packed show at the posh Oak Room at New York’s Algonquin Hotel, falling into the arms of a man in the audience whose compositions she’d long championed—Cy Coleman. Reed told the crowd that this was exactly how she’d told him she wanted to go out.

While the stylish Syms could be a prime example of this personalized kind of song shaping, she also was a jazz singer who could swing hard with jazz musicians. This fact was reflected in the evening’s mix of styles, with some artists doing one number where they focused on acting the lyric and showed their jazz-swing chops favoring melodic invention for their other appearance. At times during the evening, it was abundantly clear from the applause greeting the eclectic company that the audience consisted of people who were more jazz fans more vociferously welcoming of the harder-driving dexterity of jazz-oriented renditions, rather lukewarm in responding to some subtle, nuanced and gentler balladry. Those music fans who didn’t have one foot firmly and confidently planted in each style may have been tentatively or reluctantly dipping toes in the other genre’s musical waters. The Foundation’s Artistic Director, KT Sullivan, choosing the honoree is one step ahead with her own high-heeled fashionable shoe in stepping into the centennial anniversary of Sylvia Syms in the 2016 Convention, as Syms was indeed born in the last month of 2017. Hopefully, this will inspire more attention to be paid to the performer who had a long career, but was and is not quite as well known by the general public as some other ballyhooed nightclub stars. Fortunately, she left behind some classy albums with top-drawer musicians and chose many timeless songs and also, like Mabel Mercer, sought out rare gems, such as numbers caught from Broadway scores.

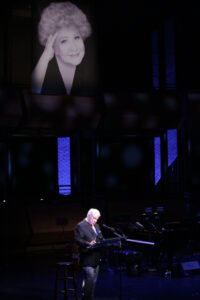

Rex Reed, acerbic and mischievous, had both the closeness of friendship and distance of time to present a personal picture of Syms not as a much-missed candidate for sainthood, but a warts-and-all funny dame “who didn’t suffer fools gladly” and had a wicked sense of humor herself.

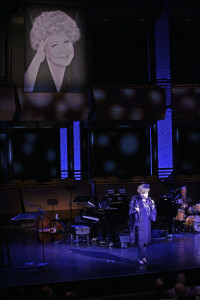

Marilyn Maye

Marilyn Maye

The first half of the night was generously sprinkled with anecdotes about 3:00-in-the-morning phone calls, a brief falling out, and quotable quips from Syms, such as her acceptance of anyone’s sexuality during earlier less enlightened times: “I don’t care what anybody else does in bed; I just wish they’d do it to me once in a while.” Syms had her marriages, her medical miseries, and her music most of all. Frank Sinatra was also a longtime friend and major admirer of her singing style (as he respected Mabel Mercer, too, famously claiming he learned “all I know about singing” from M.M. while also cheerleading for S.S.). He privately called the short, heavy singer “Buddha,” and conducted one latter-day album for her himself: Syms by Sinatra. Her very first album had Barbara Carroll as her accompanist, and it was the ever-elegant veteran who offered this evening’s first musical item: an instrumental version of “You Must Believe in Spring,” bringing an extra layer of elegance to Michel Legrand’s delicately graceful melody. It’s also the title song from the final Syms CD project, a collection of pieces with lyrics by Alan and Marilyn Bergman. The first act closed with another number included on that disc, presenting the perspective of a recently widowed woman in love with a married man who won’t leave his wife: “Fifty Percent” (music: Billy Goldenberg, from the musical Ballroom), which was thoughtfully delivered with a multi-level mix of bittersweet resignation and self-empowering determination by magnetic Marilyn Maye.

Sylvia Syms had a bit of a commercial record hit with a 45 rpm single of My Fair Lady’s “I Could Have Danced All Night” and appeared in Broadway musicals herself as Bloody Mary in a revival of South Pacific, in Whoop-Up, and a 28-performance flop, a show set in Hawaii called 13 Daughters. None of these was acknowledged in the song list, but plenty of numbers the singer recorded and did in live performances. And certainly that gave the company plenty of choices, from standards like “Skylark,” lovingly sung with the full beauty of melody and lyric by Ann Hampton Callaway, and Broadway discards, like the story-song of a little girl’s dress-up wonderment donning “Pink Taffeta Sample, Size Ten,” cut from Sweet Charity. Sally Mayes, who’d also picked up in this number in her own recording/performing career, reprised it with loving care.

Maud Hixson tenderly set the mood inherent in the title of the Rodgers & Hart classic “Isn’t It Romantic” and the same songwriting team’s “Mountain Greenery” was given a robust vocal workout by Billy Stritch, in a synthesis of splashy embellishments and joyful gymnastics mining the rich resources in past stylings of this number by Jackie and Roy, Mel Tormé (from his own solo tribute show and CD honoring that icon) and a spiffy duo version he’s done with Marilyn Maye.

Jay Leonhart (bass), Ray Marchica (drums)

Daryl Sherman, the singer-pianist, added her own insouciance and memories of Syms. Nicolas King can hardly be blamed for not knowing or having seen Sylvia Syms perform as he was all of ten months old when she died in 1992. This old soul’s early work was dynamic, but had showed heavy influences of his idols, sometimes overshadowing his chops and personality. He’s incrementally become his own man in song, but those who hadn’t recently given him a second thought sure had that chance with “On Second Thought” which he delivered with an assured maturity and interpretation with a pin-drop performance blending its intelligence into an equally pensive lamenting “Here’s That Rainy Day.” Entering after the prolonged applause that came with this performance, singer Joyce Breach spoke what many must have been thinking, simply saying: “Isn’t he good!?” The reliably lush and emotionally rich Miss Breach had already provided a highlight with an eyes-wide-open reading acknowledging “I’m the Girl” as the date a man goes to as second choice. It was a heartbreaker, and Breach was back to affairs of the heart with “My Foolish Heart.”

And there was more. Carol Woods, in sparkly attire, gamely represented the Syms mindset of soldiering on despite career downturns and serious medical problems with “Pick Yourself Up.” Jay Leonhart was in place on bass, in primo form, adding a fun vocal moment with the Murray Grand smile-inducer, the goofy “I Always Say Hello to a Flower.” And, totally comfortable in his own skin, Tom Wopat’s “I’ve Got You Under My Skin” was the pleasing picture of ease.

Not every choice seemed a good fit, some showing moments of struggle or strain, or needing more variety in their arrangements. Some shone much more in one appearance than another. Rex Reed took to song to recall a surprise song by a surprise guest friend Sylvia had arranged for his birthday—a longtime movie star fave of his: Betty Hutton. His breathy but uneasy recreation of her Frank Loesser-written “I Wish I Didn’t Love You So” was, perhaps, thrown off balance by emotional recollection. Marti Stevens’ “Mad About the Boy,” that Noël Coward multi-part opus, felt long and labored, though a notable touch of class was there. A finale having the full company sing felt anticlimactic and underprepared after the wisely included piece de resistance of an audio excerpt of Sylvia Syms’ own recording (audio only) of another Coward classic, “I’ll See You Again”—suggesting a metaphysical possibility—before the company lifted voices in song. In a concept whose payoff wasn’t worth the distraction, each singer remained onstage after his or her solo, witnessing the remainder of the show.

Rex Reed, Marilyn Maye, Nicolas King, Daryl Sherman, Marti Stevens, Carol Woods

Although a favored Syms pianist, Mike Renzi, was ill and could not participate, that unfortunate fact was offset by the high quality of those who were enlisted: Tedd Firth, Jon Weber, Billy Stritch, also known as the remaining cream of the crop. A singer’s singer, Sylvia Syms, was justly celebrated by singers and musicians alike, the audience the lucky recipients of the honoring. And even if you were quite unaware of the lady’s legacy, you got a lot of great songs, because that’s what attracted the legend. And that’s what has lasting power.