Julie Wilson

Plush Velvet, Pretzels and Beer

Cabaret Scenes, September/October 2014

by Elizabeth Ahlfors

On stage, Julie Wilson is the icon of sophistication. Her gowns are long and slinky, her hair slicked back, a gardenia tucked behind the left ear and her make-up perfect. (“It’s all Max Factor, darling. When they go out of business, that’s when I retire.”) Her songs, like her favorite foods, are often spicy and snappy, but they slice cleanly through, as if to expose the nerve with high drama and musical acuity. The audience adores her. While she has not done a planned solo cabaret show in several years, Julie Wilson remains more than the ultimate Queen of Cabaret. She IS cabaret.

More important, she is an indomitable down-to-earth spirit, proudly a “saloon singer.” When her show ends, the dress shoes come off and shaggy slippers slip on feet that had danced in the Latin Quarter and Copacabana chorus lines. Beneath the sequins and matchless command of the stage, there is a real live girl, Julia Mary Wilson, a “Svenska flicka,” from Omaha, Nebraska called “Sis.” She absorbed the values and hard work ethic from her farming parents and she learned about playing, caring and loyalty from her older brother, Russell. As in “I’m Still Here,” the song she calls “everyone’s anthem,” there were “good times and bum times,” love and loss, failure, success and tough choices, but she’s still here at almost 90, with her wide gray eyes shining and a welcoming smile. All her experiences, emotions and abundant passion are there in her songs.

Long before singing Sondheim, long before the journey of show business, even before kindergarten, little “Julia Mary” insisted on being called Mary Lou, which was a 1927 popular song on the radio. In her tomboy days, she loved singing and, even more, acting. As a teenager, she occasionally sang with a local band, Hank’s Hepcats. During her first year at Omaha University as a drama/music student, her aunt called to tell her about an upcoming audition for Earl Carroll’s Vanities. Piling her hair on top of her head, movie-star style, she auditioned for the chorus.

https://www.bodybuildingestore.com/wp-content/languages/new/flagyl.html

She wound up touring with the Vanities for six months until they reached New York City.

Now called “Julie,” she got a job in the Latin Quarter chorus in Chicago and from there a gambling club in Detroit, where she learned some hard lessons. While she thought it might be time to go back home and finish college, show biz now was in her blood, so, when she was offered another chorus job at the Latin Quarter in New York, she grabbed it. She took a brief stint singing on the road with the Johnny Long Band, but admits, “I was fired in Chicago on Christmas Eve! Our next stop was supposed to be Omaha, so I had to call my mother and tell her not to tell anyone that I was coming with the band.” Her style was too sophisticated for the band, they told her. It was back to New York.

It was wartime and making ends meet was tough. Julie lived in Queens and ate at the Automat, but, always energetic, she landed a chorus job at the famed Copacabana for $75 a week and it became a recurring home for her. She even joined the Copa USO tour to Europe. Back in New York in 1946, she was hired as a singer in the lavish Copacabana production numbers where she introduced “The Coffee Song” (“They’ve Got an Awful Lot of Coffee in Brazil”). Unfortunately, someone named Frank Sinatra recorded it first.

Back then, Julie was indefatigable.

https://www.bodybuildingestore.com/wp-content/languages/new/diflucan.html

For a while, she was performing several nightly sets at the Copa while, during the day, she sang between the movie showings at the Roxy Theatre. She relished the glamorous rush of the New York lifestyle.

Playing clubs in the 1940s and ‘50s took her to Miami where she performed briefly at Copa City and then at Mother Kelly’s. She met the versatile MGM vocal arranger/singing coach/actress Kay Thompson, who helped her forge a new, more soignée, look, slicking her black hair back into a chignon, which has remained her trademark. Also in Miami, Julie met Thompson’s agent, Barron Polan, who became the first of her three husbands and three divorces. (There was a brief second marriage.) Even after their divorce, she and Polan continued to be friends and he continued to get her jobs. Julie speaks of him still with a mixture of fondness and regret. A difficult time for her came years later when her third husband, Michael McAloney, persuaded her to end her friendship and business relationship with Polan.

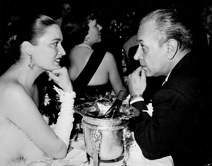

It was on to Hollywood in the late 1940s, where Polan arranged for Julie to sing a duet with Mickey Rooney on his radio show, Hollywood Showcase, which won her a two-week engagement at the glamorous Mocambo, a popular Hollywood nightclub with tropical decor and a room full of movie stars. With her sleek look and a gown designed by George Karr, who became a longtime friend, Julie was a bona fide hit.

Meanwhile, New York was luring her back. She played top clubs now: the Persian Room and the St. Regis Maisonette. Julie Wilson was the chanteuse to see, but she was also honing her dramatic skills, always her first love. She had appeared in the chorus of Three to Make Ready in 1946 and, in 1949, she found a place on Broadway in Kiss Me, Kate, replacing Lisa Kirk as Bianca, and then joined the touring company in London. (In 1958, Julie played the same part in an American television production.) She is still remembered for the show. One night, we were having dinner together at Joe Allen’s. Julie mentioned that the next night she was going to the opening of the 1999 revival of the show on Broadway. Even a half-century later, other diners at the restaurant recognized her and stopped by to tell her they had seen her in the show years ago on Broadway, or in London, or on tour.

She remained in London for four more years, moving on to Bells Are Ringing and a London musical, Bet Your Life. She cut her hair to replace Mary Martin in the starring role in the London production of South Pacific and then enrolled in the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts. Polan urged her to return to New York to accept the role of Babe in a new Broadway musical called The Pajama Game, but Julie was determined to finish her studies at RADA so the role went to Janis Paige. The Pajama Game went on to become a long-running hit. Ironically, Julie later replaced Paige’s replacement in the role she had originally rejected. It was 1969 before Julie finally originated a role on Broadway, in Jimmy, but it ran only 84 performances.

with her son Holt McCallany.

Photo: Maryann Lopinto

In 1955, she moved permanently back to New York. She had recorded her first album, Love. A screen test Polan had arranged with Sam Goldwyn led to a few films you can still catch on television. She was Ivy Corlane in This Could Be the Night and Rosebud, a blonde nightclub chanteuse, in The Strange One. She married producer and actor Michael McAloney in 1961 and had two sons, Holt and Michael, but the marriage was unsatisfying and they divorced.

The music business was also turning upside down with the advent of rock music and large stadiums and a British Invasion that replaced standard popular songs and intimate boîtes. The boys went to live with Julie’s parents in Omaha so she could work and support them and she promised she would retire to Omaha to care for them when they became teenagers.

That retirement came in 1976 when she returned to Omaha.

Holt and Michael were growing, her parents were elderly and her beloved brother, Russell, was dying. Julie took over his care at night. Her father died soon after Russell, and then her mother had a major stroke. Outraged by the hospital care and the nursing home neglect of her mother, Julie took a nurse’s aide certification course and brought her mother home for three years while raising her sons. Finally, in late 1983, the boys grown and her parents and brother gone, Julie could return to work. But where? Who would even remember her? Was there a place for her in the new music world?

online pharmacy https://www.quantumtechniques.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/jpg/valtrex.html no prescription drugstore

Just before Christmas that year, she got a phone call. Could she could be ready in two weeks to open a Cole Porter show at Michael’s Pub in New York? “Were they kidding? After all those Cole Porter shows I had done? On January 3, I was back in New York at Michael’s Pub.”

Cabarets were slowly reviving and Julie got bookings into The Russian Tea Room, The Algonquin Hotel’s Oak Room, Rainbow and Stars and top nightspots around the country. Peter Allen wrote a Tony-nominated part for her in his musical, Legs Diamond. In 1992, PBS aired a special of her cabaret show. Her energy had never failed her and she gave all she could to support aspiring talents who yearned to take the plunge into a small club with a show they have to do. If not much money, she was free to lend them her earthy sensibility, frankness and high personal standards. She gave Master Classes and she was in the audiences, shouting out “Good job!” She’s there for them as well as for old friends returning to cabaret.

I remember a late night Lainie Kazan show at the Oak Room. Julie called out for her to sing “Body and Soul,” adding “No one sings that like you, Lainie!” Kazan said, “I can’t do it. I don’t have the music here,” but she then turned to her drummer and sent him to her room to look for it. “He’ll find it, Julie,” Kazan promised. He did, Kazan sang it, and no one applauded more enthusiastically than Julie.

online pharmacy https://www.quantumtechniques.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/jpg/doxycycline.html no prescription drugstore

Julie Wilson continues to be an emblem of what cabaret aims to be, intimate moments between a performer and an audience. What makes her extra special is that she is both the perfect performer and the perfect audience.

Happy birthday, Julie.

(All photos courtesy of the Donald Smith Collection, except where noted.)